Many people have read about the controversial maternal deprivation research on baby monkeys at the University of Wisconsin, among others. One need only google psychiatric experiments on baby monkeys to see the stuff of nightmares. For me, the grave difficulty with psychiatric experimentation on non-human animals is that, for the experiments to have any real value for treatment, you must begin from the foundation that the non-human animals are psychiatrically identical or at least substantially similar in their emotions and cognitive functioning to humans. That is, that the non-human animals are sentient; that they have an identical or substantially similar emotional spectrum; that they feel the same emotions such as fear, pain, joy, loss, and so on, as humans do. If they do not, after all, of what utility is the psychiatric and behavioral research performed on them to humans? Little at best and, I argue, none. However, beginning, as one must if one is to argue in favor of these experiments’ utility, from the supposition that the non-human animals feel in the same or substantially similar way as humans do, the ethical and moral implications of treating them as one would not or should not ever treat a human in these types of emotionally and often physically violent experiments are insurmountable.

0 Comments

It is my privilege to be able to use this blog as a vehicle to share a series of stories from across the country about the American immigrant experience. More on this project here. The ninth story is: Us_me vs. Them_ME by Widelyne Laporte I was born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, which is commonly known as the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere. Which was wrongly stated by a powerful leader in America, as one of the “shit hole” countries. Before I was born, my father moved to America, leaving behind my mother and 5 older siblings, to build a better life for his family. He worked hard as a building super to live in a building for rent-free, in exchange for his services. My father knew little to no English, yet he somehow made it work, and I greatly acknowledge his hard work and perseverance. When I was 3 years old, my father was able to file for us to come to America. When we came, we lived in the basement of the building which my father worked at, for over 8 years. I remember this building being infested with rats, mice and flying roaches. We started off sleeping on the floor to my father saving enough to buy one bunk bed, which was shared amongst my sister and I. We made the best of our living lifestyle. Despite of our living conditions and being an immigrant, I was not embarrassed at a young age. However, as I got into elementary and junior high school, students often made cruel statements about immigrants. About me. At that time, there was a rumor spread that Haitians were bringing HIV/AIDS to America. Often times I would be told to go back home and called names because of what I wore and what my parents could not afford. I did not ever feel like I was an estranged person, an outsider, or loner until I started school. But, my lack of embarrassment of being an immigrant had a lot to do with my parents. My parents always spoke Hope and Faith in our God. Always said, “this was TEMPORARY. Everyday is a stepping stone.” My father is now the owner of a house, my older siblings married with kids, in their own homes with promising careers. And as for me, I am working as a nurse, giving back to my parents for their hard work and sacrifices. I am also giving back to the country that has given me the opportunity that I might not have had in my country, Haiti. I am a hard-working individual and also helping American citizens in a country which I was not born into. Being in the healthcare industry, caring for people of all ages, races, and ethnicities, I’ve learned a powerful thing; no matter what we are, we all are born into a world and will die into a world. Therefore, there shouldn’t be divisions, separation, inferiority, and human rights violations. The way immigrants are being treated with injustice is inhumane. Yet, it is the same immigrants as myself, who are able to give back and help PEOPLE as a whole. Widelyne Laporte

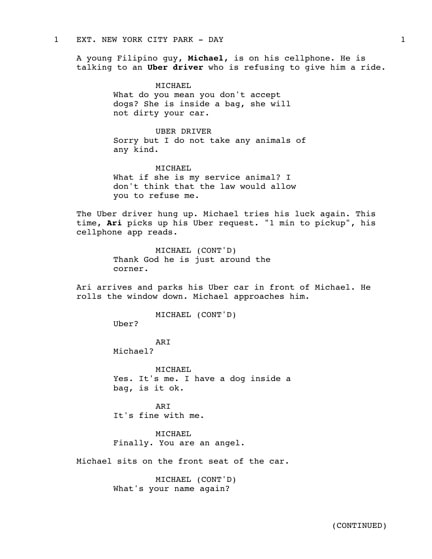

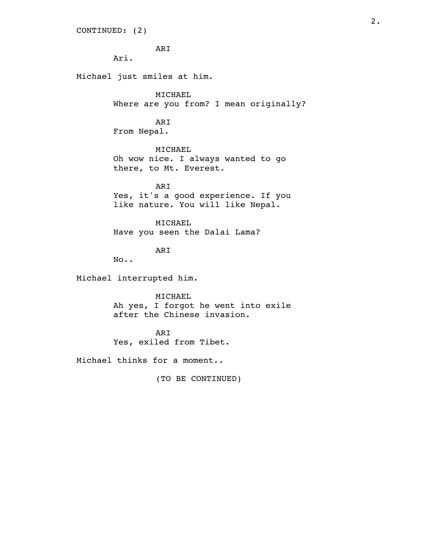

Widelyne was born in Haiti and migrated to the United States at the age of 3 with her mother. Widelyne is now a citizen, a licensed practical nurse and an actor. Facebook.com/widelyne.laporte **Special thanks to Ricardo Arechiga for his graphic design of the project logo**  It is my privilege to be able to use this blog as a vehicle to share a series of stories from across the country about the American immigrant experience. More on this project here. The eighth story is by Valery Valtrain: Like most children immigrants, I didn’t have any say in the big move to the United States of America. For some children, the move may seem like an adventure. But for others, the adventure involves leaving behind all that was once familiar in order to try to adapt to a world that even your parents are lost in. My mother, the only parent I’ve ever had, relied on me so much so; it sometimes felt as if we had somehow switched roles. Slowly, I began feeling the burden of being responsible for my mother. Feeling like it was my duty to ensure she was able to navigate around this new world, since I was the one adapting to it with greater ease. I grew up sooner than most. After all, I was responsible for so much more. I was often praised for having more maturity than my peers. Such is the life of an immigrant child. There is a duality to our nature that most of our peers could never embody. Our minds have to think in twos, always translating from one dialect to another. Always having to remember whom it is we are speaking to in order for the correct language to be spoken. We have to see the world through the lenses of our audience in order to ensure that we can truly relay the messages we are telling them. It often makes us more empathetic and more selfless. I bond better with people. I believe many immigrant children have an understanding of the world around us that most aren’t privy to. We are analytical by nature because we had to study the world around us more than once. We have to first make sense of the world for our own comprehension, and then have to continuously revisit it to explain it to our parents and anyone else in our families that aren't able to quite grasp it. We take in all of the information the world has to give and then we must scrutinize it in order to share it. Such a role, causes you to be attentive, to listen, to care, Perhaps that is why strangers tend to share intimate details about their lives with me, and friends often seek my advice. Feeling compassion for others, seems to be a constant with immigrant children whose roles mirror my own. We are given the task to be responsible for our parents and in the process, we tend to feel responsible for the world. Valery Valtrain Val Valtrain is a writer, a mother, an American, an immigrant, and the daughter of immigrants. She is interning with the Film Lab. **Special thanks to Ricardo Arechiga for his graphic design of the project logo**  It is my privilege to be able to use this blog as a vehicle to share a series of stories from across the country about the American immigrant experience. More on this project here. The seventh story is by Rosa Soy: I arrived in the United States on February 9, 1962, a day forever etched in my memory. I was sent here by my parents through the “Peter Pan” program, curiously named after a boy who would not grow up, which allowed children from Cuba to be welcomed to the U.S. The political undertones of this project were, of course, unknown to us at the time. Having been uprooted from the relative comfort of our middle class lives, we were called “refugees,” and placed in shelters, orphanages, and foster homes. We came alone without our parents who, we were told, would later join us. The program had the dual purpose of embarrassing the Castro regime, and protecting us, so that we would not be taken from our family and sent to the Soviet Union. Our parents assured us this was only temporary and they would join us in a short time. Temporary or not, the wounds of separation left lifelong scars. The interrupted childhoods the loss of homes, relatives, friends and pets, all that was familiar and dear to us, took its toll. The promised protection came with a price -- separation from those we loved the most. And, as our parents encountered numerous obstacles to our reunification, the separation was often unbearably long and painful. In spite of Peter Pan, we did grow up, apart from our families, making choices we did not always understand. We learned to relish our independence as immigrants to this nation. We mastered a new language, became accustomed to new landscapes, tastes and smells. Grateful for our good fortune, we pledged allegiance as new citizens, while longing for the people and places we had left behind, which had slowly begun to fade from our memories. Today, as an immigration attorney, I am often taken back to the pain and struggles of the early years. But I am rewarded by assisting a new wave of young people who long to be accepted and welcomed as immigrants to their new land. Rosa H. Soy Rosa Soy received a “Meet the Composer” grant for the “Future Feminine”a mixed-media project, and is the co-writer of The Rose Slippers,a children’s musical, an award recipient of the 2004 Jackie White Children’s theater competition. Rosa’s plays Esperanzaand The Planhave received staged readings at New Jersey regional theaters. Her play Venial Sinswas selected for the 2004 Samuel French festival in New York. And her short playPigeonswas presented at the 2005 Samuel French festival in New York. Her play “Off Balance” was presented at Luna Stage Theater Company in Montclair NJ. Rosa served as playwright in residence for Passaic County Community College during 2009 and 2010. She is currently working on a book about her experiences as an immigration lawyer. **Special thanks to Ricardo Arechiga for his graphic design of the project logo** It is my privilege to be able to use this blog as a vehicle to share a series of stories from across the country about the American immigrant experience. More on this project here. The sixth story was submitted in script format and is here: Roman Sotelo

Roman Sotelo is a graduate of Digital Photography and Imaging in Pratt Institute and Digital Cinematography in New York University. He is currently studying Filmmaking in School of Visual Arts. www.romansotelofilm.com  It is my privilege to be able to use this blog as a vehicle to share a series of stories from across the country about the American immigrant experience. More on this project here. The fifth story is: George by Riti Sachdeva In the mid-1980s, when I was in high school, my parents bought a house and moved us to a very white suburb (vws) just outside of Boston. In the svws, I went to a very white high school (vwhs), where I played the violin in the orchestra. Being a vwhs, every spring, the orchestra took a trip to play a concert in a different community. My sophomore year,the orchestra was invited to play at a high school in Montreal. From the vwhs, we were three busloads of students, chaperones, and instruments… and three bus drivers. The driver of the bus I rode was named George. He was dreamy with sparkling eyes, mischievous smile, and a super sexy goatee. He was probably in his mid to late twenties, so in my teenage fantasies, he was the “perfect age.” At fifteen, I was the perfect age for social and physical awkwardness. I had braces, an unruly head of coarse black curly hair, brown skin, big tits, big hips, and a big ass. No matter how hard I tried to have a cool American wardrobe, it just seemed bumbling on my body. For the entire trip to the Canadian border, the girls on the bus flirted with George. I wouldn’teven make eye contact with him, knowing that trying to be as charming or beautiful as the white girls would just end in my humiliation. At the U.S.-Canada border, all three buses stopped to go through Canadian immigration. We sat around for a bit before a Canadian immigratio nofficer stepped into the bus wanting to know: Was there anyone who was not a US citizen? I was the only brown black yellow or red student on all three buses. I don’t recall if the officer was looking directly at me…I raised my hand and volunteered my immigration status. He approached me. Are you a permanent resident? Yes. Do you have your green card with you? No. Come with me. As I walked on the bus, terrified, I made eye contact with George for the first time. He held my gaze, unwavering. Three busloads of impatient vwhs students watched me and the Canadian immigration authorities enter a building where I was interrogated for an hour. Why didn’t you bring your green card? I didn’t know. No one told me to. Country of origin? India. When did you come? 1975…? Who did you come with? My parents. Where have you lived? Parents names? Occupations? Mother's maiden name? They checked through records on what was a computer back in the mid-1980s. My green card number, my mother's green card number, my father’s greenc ard number, my parents' employers, other relatives in the U.S. When, finally, they were satisfied that I was not a Sikh terrorist nor would I try to defect, they approved my entry into Canada. I walked back to the bus wearing the stunned humiliation of being an Other: a registered alien, immigrant, brown teenager amongst three entire busloads of white people, except for the three Black men driving the three buses. I stepped back into the bus and felt the hostile silence and impatient stares from the very white high school students. I looked at George, big tears thrusting their way to the surface of my eyeholes. He welcomed me with his shining eyes and uttered the one thing that could revolutionize the indignity of the moment. He spoke a spell I carry, still, in the lining of my super hero magic…George grinned wide, "It takes a special lady to hold up three buses.” Riti Sachdeva www.ritisachdeva.com IG: @midniteschild YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCrBSU9I7zOWxERjC1fPnAwQ/featured?disable_polymer=1 **Special thanks to Ricardo Arechiga for his graphic design of the project logo**  It is my privilege to be able to use this blog as a vehicle to share a series of stories from across the country about the American immigrant experience. More on this project here. The third story is: Home of the Brave by Avantika Rao, Attorney I am a longtime asylum and immigration lawyer who has worked with immigrants from Zimbabwe to Argentina. While U.S. immigration law is historically oppressive and exclusionary, I use the law to multiply freedom, to unite immigrants with their family, to allow longtime immigrants to be able to vote and participate as U.S. citizens, and to protect those who have been dehumanized due to their dissident or minority status. While I am a joyful spirit, I have experienced and been witness to more suffering than most could conceive. I am myself a survivor of virtual captivity and I work with immigrants and torture survivors from all over the world. I also recruit and mentor diverse attorneys to stay in the legal profession despite life-threatening challenges such as burnout, prejudice, and addiction. I am still haunted by the memory of the Salvadoran trans woman who had been disowned by family, tortured by police, and was enslaved as a performer in Mexican cantinas. Despite being jailed with the men, living with HIV, and suffering a stroke, she continued to send me drawings of Catholic saints with halos and hearts, adorned with messages of love and gratitude. She lost her claim for protection as a persecuted sexual minority. The white male immigration judge stated that she had a “victim complex” and blamed her for not remembering either her prior political asylum claim or details of the traumatic events. Judges can embody prejudice, transphobia, and patriarchy in their black cloak. She had been raped so many times that she had blocked entire years out of her memory. While intense trauma is not uncommon among the asylum seeking population, what is heart opening is the myriad ways in which immigrants and asylum seekers bravely overcome. Over the years, there were children and families from all over the world, crime survivors who qualified for visas after they cooperated with law enforcement investigations, political dissidents, girls or women or sexual minoritiesescaping forced female genital mutilationor domestic slavery or sexual assault, those whose nations were engulfed in deadly civil strife, those whose particular social groups made them subject to persecution, and those who wanted to reunify with their family, work in the United States, or be united with an immigrant they had fallen in love with. I recently worked with a Nigerian woman whose bravery clarified for me the profound reason why I do this work. She had been through absolutely horrific domestic violence and stalking. Yet, she was so strong, sure of herself, and positively effervescent. In a tribal marriage custom of Nigeria, the husband pays the bride’s family a “bride price” at the time of marriage. The return of that money finalizes a divorce. A husband can block a divorce by refusing the returned bride price. This is what happened in this woman’s situation. As a daughter of Indian immigrants growing up in suburban Los Angeles, my childhood had largely consisted of me witnessing my father turn my mother into a virtual captive through aggressive assaults, verbal degradation,restrictions on food and finances, and isolation. The tactics were even harsher when unleashed on us childrenbecause we had no way to defend ourselves and had no money of our own. It was a prison like atmosphere. He tied me up with ropes and left me locked in dark rooms. Food and clothing rations were given in an atmosphere of coercion and penance. He gave in to my pleas for pet dogs only to chain them up in the yard and flagellate them when they barked with loneliness before dropping them back at the shelter. If I asked for a Christmas decoration or a Halloween costume, I would get verbally assaulted for weeks before he would find something so incredibly cheap and ugly that I would conclude that I should not have asked in the first place. My father created an elaborate facade. He was the quite literally the P.T.A. President. I recall the evening that I witnessed my father drag my mother down the stairs by her hair and, fearing for her life, called the police. Two male L.A.P.D. officers stood outside on the stoop. “Is everything fine?” The abuser stood an inch or two away from her, quivering with rage. He had already torn the phones out of the wall. She nodded. I was mercilessly punished for trying to save my mother's life. My school books torn up. Assaulted and terrorized. Forced to give up any hard-won scholarship monies received. In my diary, I recorded the moment that I realized that my mother would never leave. I had come home and the abusive episode had already occurred. Adead feeling in the air. My father said authoritatively to my mother, “No one will ever believe you because I talk nicely to everybody.” She went to the front door of our home in Los Angeles. She opened the door. She let out a primal scream. Then, she closed it. She never sought refuge in a domestic violence shelter. She shunned counseling. She and my father constantly insulteddivorced women. She boasted about the dozens of invitations to lavish weddings and social events she got each yearfrom people she barely knows because of her status as a married woman in the local Indian immigrant community. Inside, she remains paralyzed with fear andshame, never wantingher toxic secretsrevealed to an adjudicator or discussed by the other Indian immigrants we socializewith. The fear and shame is still infused inevery fiber of her body. A code of silencehidden in ever larger and more luxurious homes and encircled by an invisible mental fence. In my work to free survivors of domestic violence and human trafficking, I often come across grooming, justifications, and feedback loops that enable the abuse. Each abuser has their own ecosystem. Manyin the ecosystem, including the victims,act as apologists and enforcers for the abuser. Those targeted for abuse quite frequently either numb themselves through addiction or perpetuate the abuse. Abusive ecosystems replicate themselves. I recently observed to my mother that it was not that she ever made an affirmative decision to stay, but that she quite simply never developed the courageto leave. “I agree, I am not brave,” she replied. Bravery is developed in the face of challenge to life or freedom. There are many alternatives to developing bravery. Self-pity, obsessing, or distraction. Workaholismor rescuing behaviors. Self-neglect or self harm. Harming othersthrough abuse. Adictive or compulsive behavior. Enmeshment. Perfectionism. Drama. And there is always the option of remaining paralyzedin fear and shame. The Nigerian womanhad unsuccessfully reported the abuse to the police and a human rights commission. The police had said, “Go back to your husband, madam.” Neither had reined in the abuser, much less investigated the matter. I asked what it was that sparked the Nigerian woman’s decision to flee. She said she hadread articles about domestic violence. She realized that itwas a major social problem, indeed a life-threatening one. Though she had attempted to get her daughters passportsto be able to travel with her, her abuser used their two young daughters as leverage. After she fled, her abuser sent achilling message with a photo of the girls’ passports stating that she would never see her children again. She fled to the U.S. without her two daughters. At the time she fled, her girls were not even old enough to attend school. I filed for gender-based asylum for her. We won. However, her ordeal is far from over. Her gaining asylum is just the first step in a long fight to petition the legal system for her daughters to be reunited with her. In the Nigerian courts, from what I have read, it is a system in which the father’s power over custody and family decision making power is assumed. When she read the articles, she realized that her very life and freedom wereat stake. In her flight to freedom, she, like many of the courageous immigrants I represent, exemplifies bravery. I hope that one day I get to witness the smiles of her two daughters holding their mother’s hands in the home of the brave. Avantika Rao Avantika contributes to spiraling up justice through direct service (particularly to immigrant survivors of domestic violence, sexual assault, and/or modern-day slavery), uplifting diverse candidates into the legal profession, and collaboratively detonating injustice and prejudice. Avantika has defended (adult & child) immigrants at the US-Mexico border and served as a founding attorney in San Francisco's immigrant defense network. Her Sacramento-based law practice operates at the intersection of immigration & human rights. Prior to law school, Avantika studied environmental and gender policy in the U.S., India, & Nepal. She prefers milk chocolate to dark. **Special thanks to Ricardo Arechiga for his graphic design of the project logo**  It is my privilege to be able to use this blog as a vehicle to share a series of stories from across the country about the American immigrant experience. More on this project here. The second story is: NOT QUITE by Ada Cheng, Ph.D. On May 27, 2015, my guests and I arrived at the USCIS building in downtown Chicago right before 1 PM to attend my citizenship ceremony. There was a long desk inside the entrance of the ceremony hall and three agents were sitting there. When it was my turn, the first agent took my green card and my notice. The second one examined them and threw them into this big yellow envelope while the third one checked my name off a list. My heart sank when I turned in my green card. This was the only legal documentation in my possession to prove that I was documented or legal in this country. At that moment, I was without any documentation. I suddenly became an “illegal” in the eyes of the state. I started to panic as I walked into the big hall, where hundreds of immigrants like me had already been seated. It was very scary to be with hundreds of people without legal documentation. It was as if we were waiting for our collective sentence. Theoretically, any one of us could be arrested, locked up, and deported right there and then. But deported back to where? It has been more than two decades since I left Taiwan in 1991. I have family there, but it has not been my home for more than two decades. Going back there is not going home. But then where is home? My heart pounced every time an agent walked toward my direction. I kept thinking to myself: Is this all a trap? Is the agent going to tell me something was wrong with my application and they changed their mind about naturalizing me? Did they not believe me when I told them during the interview that I didn’t torture anyone, that I didn’t engage in genocide, that I did not intend or attempt to overthrow the US government, that I was not a communist, that I was not a terrorist, that I was never in prison, that I never committed felonies, that I was not a gambler, that I was not an alcoholic, that I did not abuse any drugs, that I didn’t force anyone to have sex with me, and that I didn’t solicit sex? Suddenly, I saw my guests enter the hall and take their seats. After a few minutes, the director walked up to the podium and announced that the ceremony would begin. I felt a sense of relief. When we were watching the documentary, the narrator talked about how fortunate it was that we, like previous generations of immigrants, escaped war, poverty, and political and religious repressions, to come to this country to pursue the American dream. I immediately felt terrible that I invited my colleague to the ceremony. You see, my colleague was a 70-year-old African American man. His ancestors didn’t come to this country voluntarily. What was my celebration was not necessarily his to have even though he was very happy for me. Our stories were connected yet very different. I got through the ceremony and eventually received my certificate of naturalization. This certificate has two numbers. It has the number for the certificate. It has another number A#########. Do you know what that A stands for? I didn’t even realize the significance of these two numbers until when I tried to apply for the Affordable Care Act health insurance in December 2016. They asked for both numbers on the application when I identified myself as a naturalized citizen. That A stands for alien. That’s my Alien registration number. A number I carried for decades before becoming a citizen. You see, those numbers are for registration, and there is always a registry for aliens. I am forever reminded of my Alien status every time I am asked for them. Most people would assume that the process of naturalization enables immigrants like me (let me be clear, a very privileged one) to assimilate into this country, become part of this country and finally be home. I have contributed to this country by educating young people at the university for 15 years. Here is the irony. Not as a citizen, but as an immigrant. First on my H1B visa and then with my green card. This country has entrusted immigrants with many of her most important jobs, including raising children, caring for the sick, and educating young minds, yet we are forever unwelcome. As much as I try to blend in by achieving the American dream, this country or shall I say this government is never going to let me forget that I am indeed an Alien and I will forever be one. So this is my American journey. My American dreams pursued and achieved, but I am still not home. Shu-Ju Ada Cheng Ada Cheng is a professor-turned storyteller and performing artist. She has been featured at storytelling shows in Chicago, Atlanta, Cedar Rapids, New York, Asheville, and Kansas City. She debuted her first solo show, Not Quite: Asian American by Law, Asian Woman by Desire, in January 2017, which later received a great review from Washington Post. She debuted her second solo show, Breaking Rules, Broken Hearts: Loving across Borders, with Fillet of Solo in January 2018. In addition to performing it at The Exit Theatre in San Francisco in June, she will also bring it to the United Solo Theatre Festival New York in October this year. Ada is the producer and the host of the show, Am I Man Enough: A Storytelling/Podcasting Show, where people tell personal stories to critically examine the culture of toxic masculinity and the construction of masculinity and manhood. She is also the co-producer and co-host of Talk Stories: An Asian American/Asian Diaspora Storytelling Show, a show that features Asian/Asian American performing artists and storytellers. Her motto: Make your life the best story you tell. Her website: www.renegadeadacheng.com. **Special thanks to Ricardo Arechiga for his graphic design of the project logo**  It is my privilege to be able to use this blog as a vehicle to share a series of stories from across the country about the American immigrant experience. More on this project here. The first story is: HOMELAND by April Xiong My mother came to America two years after my father did, while already pregnant with my older brother. Last year, she reached the strange intersection of having spent exactly half her life in China and half her life in America. Years before that, she had renounced her Chinese citizenship to become a U.S. citizen, though not for any idealistic reason. It was purely a practical decision: having a U.S. passport would make it much easier to travel to Europe, a destination long dreamed of. Last summer, she finally got her chance. Having worked hard all her life, my mother is starting to take more of an interest in material pleasures. My father, unlike my mother, has never given up his Chinese citizenship, and likely never will. He sings the old songs when he cooks. He tastes China in the hot steaming food he prepares out of the cold produce of our American refrigerator. He often takes business trips to Chengdu, returning to the land of his birth with a secret smile and a feeling of relief. To speak his own language again, to be with his own people, who understand him. I do not understand him, though I try. The story goes like this: my father came to America to earn his Ph.D. in mathematics at Ohio State University, the only place he was accepted. He landed in San Francisco in the dust of Chinese footsteps, two years before my mother, carrying my brother in her womb, followed him to our land of the free. He arrived in the city with only $50 and an enterprising spirit to his name. The first night, he spent $35 of his $50 for a hotel room and a meal. Ever the mathematician, he quickly saw that he would have to increase his funds; the next day, he went and borrowed $300 from the Chinese embassy. With that princely sum, and with the $15 he had left from his original supply, he flew to Ohio to begin his new life there. The trip used up all of his money, borrowed money included. Fortunately, he had a teaching assistant position at the university that paid for housing, food, and tuition. He lived in an apartment building near campus, and his room was very small—just big enough for a desk, a bed, and a TV. He claims he was very happy in those days. He tells the story straight, as he always does. Straight, without embellishment. Everything must have been exactly the way he tells it—black and white, no grey. He demands the utmost clarity in everyone and everything around him. This inflexible quality is surely a byproduct of his mathematical background. So used to the perfect, elegant succinctness of equations and numbers, he must find this strangely-shaded world of ours a bewildering and inefficient place. As for me—who staggers around in a perpetual state of obfuscation—he looks at me, always, with furrowed brows and a faint look of disapproval. In his eyes, am I a theorem waiting to be proven? Do I puzzle him as much as he puzzles me? I wonder what my life would be like now if I had been born, and grown up, in China. Would I have the same values, beliefs, interests, dreams? Maybe I would be a doctor, like my mother, or a mathematician, like my father. The truth is, I wouldn’t have been born. Due to the one-child policy, my parents would have stopped having kids after my brother. I wouldn’t be alive now if they had stayed in China; I owe my very existence to the fact of their immigration. Grateful that I made it into this world at all—here I stand on my line of love, looking back-and-forth between two cultures, two nations. On one side lies the land of my kin, the land that my parents never truly left behind, the land that I long to know…on the other side lies the land of my fellows, the land that I can never truly leave behind, the land that I have known. Here I find my homeland—here on this line of love. April Xiong April Xiong is a writer, director, and editor. Her short film "Drive," adapted from the poetry of Hettie Jones, was featured in the 2018 Visible Poetry Project. Having traveled the world in search of unheard stories, she is devoted to exploring the voice of the other in her writing and films. Instagram: @april.xiong Facebook: @april.q.xiong Website: https://www.aprilxiong.com/ Vimeo: https://vimeo.com/aprilxiong **Special thanks to Ricardo Arechiga for his graphic design of the project logo** |

Jen YenActor, Author, Attorney Archives

June 2024

Acting, Writing & Producing

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed